Expand Your Photography with Specialty Lenses

Today, many digital photographers start with a point-and-shoot camera and work their way up to an SLR. If that was your path, you may not be familiar with the more obscure lens types. Because you can choose what type of lens to put on an SLR, you can opt for different focal lengths, upgrade to a higher quality lens, and choose lenses based on weight and size. All of these options give you a tremendous level of flexibility.

Let’s look at five specialty lens types:

- Fast

- Wide

- Fisheye

- Lensbaby

- Tilt and Shift

Fast Lenses

Fast lenses aren’t so unconventional, but they can greatly expand the conditions under which you shoot.

When I speak of a lens’ speed, I’m not referring to how quickly it can autofocus, or how speedy its zoom is, or how fast you can get it on or off of your camera, but rather the widest aperture the lens can be opened to. With a faster lens, you can shoot in low light without compromising your shutter speed (Figure 1), and you can shoot extremely shallow depth of field.

Figure 1. Though it was extremely dark in the room, I got a bright, steady shot thanks to the f/1.2 lens on my Canon EOS 5D.

Almost all lenses list their widest aperture on the end of the lens barrel (Figure 2). Zoom lenses typically show a focal length range that specifies the maximum aperture at both the widest and longest focal lengths. So, for example, a lens rated at f/4-5.6 can shoot at f/4 when zoomed out all the way, and at f/5.6 when zoomed in all the way. The middle focal lengths vary as you zoom.

Figure 2. The ends of most lenses have markings that indicate the widest aperture of the lens. In this case, the widest aperture varies from 3.5 to 5.6.

A lens that can shoot with a very wide aperture requires a lot of glass — a lot of very high-quality, heavy glass. Faster lenses tend to be larger and heavier than slower lenses. If you’ve wondered why one 70-200mm lens sells for $700 and another 70-200 lens sells for $1,600, it’s most likely because the second lens can shoot at a very wide aperture across its entire focal length range.

You typically won’t find zoom lenses that go much faster than f/2.8 or f/2 because it’s simply too complicated and impractical to build a zoom lens that can go faster than that. However, f/2.8 is nothing to sneeze at. An f/2.8 lens will let you shoot in low light with zippy shutter speeds, and allow for shallower depth of field than what you’ll find at f/4.

With prime lenses, though, you can go quite a bit faster. (A prime lens has a fixed focal length.) For example, an f/2.0 50mm lens is one stop faster than f/2.8, meaning it lets you shoot with a shutter speed that’s twice as fast as the shutter speed you could shoot with at f/2.8. An f/1.4 lens gives you another stop, and an f/1.2 gets you an additional half a stop.

The major vendors aren’t making lenses faster than f/1.2. (In the past, Canon has made lenses as fast as f/0.95.) However, Canon’s excellent f/1.2 50mm is a great option when you need to shoot in very low light, or want shallower depth of field effects than what you can get now. Similarly, Canon’s f/1.2 85mm yields a focal length that’s ideal for portrait shooting.

Lenses with an f/1.2 aperture are fairly large and very heavy, so it’s a good idea to get your hands on one before you buy and make sure you’re willing to carry it around (Figure 3).

Figure 3. On the left, the Canon 50mm f/1.2; on the right, the Canon 50mm f/1.8. As you can see, the faster lens is a bigger, heavier lens.

While the extra half-stop is nice, f/1.4 and f/1.8 lenses also afford plenty of low-light shooting power and are typically smaller and cheaper than f/1.2 lenses. Both Canon and Nikon make 1.4 and 1.8 50mm lenses, as well as 85mm lenses.

If you like shooting in low light, a faster lens can be a great addition to your camera bag.

Wide Lenses

The human eye has a field of view that’s roughly equivalent to the field of view of a 50mm lens on a 35mm film camera. A lens with a longer focal length will have a field of view narrower than what your eye sees, while a lens with a shorter focal length has a wider field of view.

A 35mm lens is ideal for street shooting because it allows for a slightly broader view than what you get with a 50mm. Landscape shooters tend to go a little wider, usually around 28mm. Between 28mm and 16mm, you’re in the realm of the “super wide.” Most super-wide zooms have focal length ranges of around 16 to 35 mm.

A super-wide zoom lets you shoot a tremendous field of view, which is well-suited to landscape work or to capturing a broad view of a space (Figure 4). It can also be used in place of a regular lens for an interesting perspective (Figure 5).

Figure 4. A super-wide lens captures extremely wide vistas for unique perspectives. Click on the image for a larger version.

Figure 5. A super-wide lens isn’t just for shooting landscapes. Click on the image for a larger version.

Remember, though, that your particular SLR might use a sensor that’s smaller than a piece of 35mm film. This cropped sensor has a field of view that’s narrower than what you’d get on a piece of 35mm film or on a full-frame sensor. In those cases, you need to multiply the focal length of a lens to determine its 35mm equivalent focal length.

Most Canon SLRs have a focal length multiplier of 1.6, while most Nikon SLRs have a multiplier of 1.5. So, a 50mm lens on a Canon cropped sensor SLR has a 35mm equivalent focal length of 80mm, while a 50mm on a Nikon has an equivalent 35mm focal length of 75mm.

It used to be difficult to get wide-angle lenses for cropped sensor cameras, but that’s no longer true. For example, Canon’s 10-22mm lens is equivalent to a 16-35mm lens on a 35mm camera. Note that you can’t take a lens designed for a cropped sensor camera and use it on a full frame or 35mm camera.

Making a super wide-angle lens is very tricky, as it can be difficult to engineer away geometric distortion at the edges and corners of the frame. The lenses I’ve been discussing are “rectilinear” lenses; that is, they’ve been engineered to correct the extreme distortion that can occur at wide angles. However, there are other types of wide-angle lenses that don’t provide this type of correction, which I’ll cover in the next section.

Fisheye Lenses

A super-wide lens that doesn’t include geometric correction is a fisheye lens. Why would you intentionally shoot with a lens that introduces warping and distortion? Partly because it looks cool, but also because it can give you an even wider field of view than a rectilinear lens of the same focal length (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A fisheye lens allows you to shoot even wider than what you can capture with a rectilinear super-wide lens, albeit with some extra geometric distortion.

Canon and Nikon make excellent fisheye lenses for both cropped and full-frame sensors. These lenses offer an extremely wide field of view, and while they’re distorted, they’re not nearly as distorted as traditional fisheye lenses. Plus, you can use Photoshop to correct a fair amount of distortion in the images (Figure 7). Nikon Capture NX will even perform this correction for you if you’re shooting with Nikon’s excellent 10.5mm fisheye lens.

Figure 7. You can often correct fisheye distortion (top image) using software, which results in an photo that’s closer to a rectilinear wide angle (bottom image).

As you can see, when you correct the distortion, you end up with a cropped image, one that has a field of view more like a super-wide rectilinear.

Lensbaby

The Lensbaby is a very affordable ($100 to $400, depending on the model you choose) option with a unique effect. The Lensbaby is a lens mounted on the end of a bellows. The bellows lets you tilt the lens to change the center of focus and create cool smearing effects.

Figure 8. The Lensbaby is a selective-focus lens for capturing images that look smeared and distorted.

Obviously, the Lensbaby isn’t for everyday use, but for those times when you need to stylize an image, add a sense of motion, or bring an extreme amount of focus to just one part of a scene, it’s a great tool (Figure 9).

Figure 9. With the Lensbaby, you can create stylized, dynamic images. Click on the image for a larger version.

The Lensbaby also works with several add-ons and attachments, including a wide-angle adapter, and some very handy macro lenses. Macro shots always have extremely shallow depth of field, so the defocusing effects of a Lensbaby aren’t as noticeable when shooting macro. Because of this, a Lensbaby and matching macro filters make a very good, very inexpensive macro option (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The Lensbaby also supports inexpensive filters that yield nice macro shots.

Tilt and Shift Lenses

Tilt and shift lenses provide a tremendous amount of power for anyone who shoots architecture, interiors, or any other situation that requires a control of perspective. With a tilt and shift lens, you can shift the front element of the lens up and down, as well as side to side, to correct for perspective (Figure 11). While not as versatile as a view camera that also lets you move the rear of the lens, a tilt and shift lens is much smaller and easier to work with.

Figure 11. Using a tilt and shift lens, I corrected the perspective in this scene so that the vertical lines are closer to vertical. Click on the image for a larger version.

Using a tilt and shift lens takes practice. It’s easy to throw part of your image out of focus, and it’s difficult to check focus in the viewfinder, or on your camera’s LCD screen. Also, these lenses are fairly heavy and definitely expensive. Before you invest in one, consider renting it from a vendor, such as rentglass.com.

These days, it’s easy to get focused (Ha. Ha.) on all of the cool things you can do to your images in post-production. Don’t forget that your camera itself has a wide range of capabilities, depending on the lens you choose.

This article was last modified on December 14, 2022

This article was first published on November 28, 2007

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

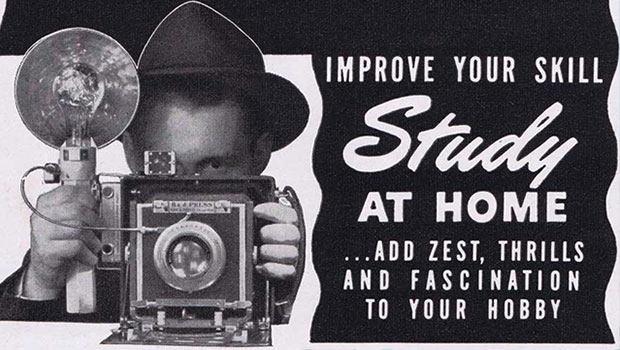

Scanning Around With Gene: Stuff I Miss About Photography

For my thirteenth birthday, my father gave me a “junior darkroom” kit and taught...

Lightbox Photography Cards

In the past, we’ve seen plenty of cool Kickstarter projects to create deck...

8 Tips for DSLR Video Beginners to Shoot Great Video

Video is more accessible today than it has ever been. DSLR cameras with intercha...