Going with the Flow

Creative professionals use some of the most-sophisticated software there is — cutting-edge programs that do truly amazing things. But none of the software we work with is as cool (or as cool looking) as the software that the characters in our favorite action movies and forensic-investigation TV dramas use — whether they’re hacking encrypted CIA files or just sending an instant message.

So say you’re a software developer working on a new kind of app, and you want to express its uniqueness with an interface like nothing we’ve seen before. When Steve Forde, the president of GridIron Software, found himself in that position, he turned to Mark Coleran, a visual designer who has designed the computer screens and interface effects for many films, including “The Island,” “Children of Men,” and “The Bourne Ultimatum.”

Figure 1. Mark Coleran created this screen for the dystopian thriller “Children of Men.” He says that he relishes opportunities to explore futurism — to take a close look at today’s software and then figure out how it might evolve, given a filmmaker’s vision of the future. Click on the image to see a larger version.

GridIron’s new app aims to revolutionize the way creatives handle complex workflows. Flow, which is slated for a summer 2008 release and was previewed at January’s Macworld Conference and Expo, is a next-generation content-management system that automatically records relationships (such as import, export, copy, and paste) between a project’s assets and applications. With calendaring, version-control, and other helpful features, Flow is meant to function as a sort of dutiful, obsessively detail-oriented assistant who can unobtrusively document and diagram the thousands of pesky workflow details in a complicated creative project. The program’s map displays file relationships, and even lets you preview a file’s fonts, color swatches, and more.

But this complex program had to look simple and intuitive — and because it was meant for an audience of creative pros, it had to look good. So it presented its developers with some difficult user-interface requirements. Forde explains, “When we started looking at all the ways that we could interconnect things, we faced the prospect that users were going to launch their data from Flow and live within it a lot, not just use the tools.”

Forde approached Coleran at an IBC conference in Amsterdam and asked for Coleran’s feedback as a potential Flow user. But Coleran’s ideas gave Forde an idea of his own: “I showed him what we were working on,” Forde explains, “and he talked about a couple of ideas that he had. And after talking to him, I just came out and said, ‘Do you want a really interesting challenge?'”

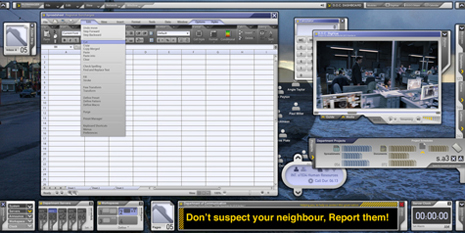

Figure 2. Coleran designed the software interfaces seen in the sci-fi action movie “The Island.” “One reason I got involved in Flow was that I got so frustrated with files and folders,” he says. “When I first started doing this work 18 or 19 years ago, a job would have two or three files to it. When I backed up ‘The Island,’ I think it was 20,000 files in total.” Click on the image to see a larger version.

Although Coleran had worked on true user-interface design before Flow, he says that Flow is the first “professional” thing he’s done in this area. He was excited about adding to an application that would make his work significantly easier: “The major innovation here is that Flow allows you to see how a piece of work was put together. You see everything as a whole rather than as individual pieces… and I was sold on it instantly when I saw one of GridIron’s original tech demos.”

He describes working on Flow’s development as a fantastic challenge: “I came up here to do a week’s work, just brainstorming concepts and ideas — and I actually thought it wouldn’t require that much. For a typical film, I sometimes have three months to produce 200 screens. For this, I only had to produce one — but 12 months later, I’m still working on that one screen.”

And after that year of work, GridIron’s Forde says that there isn’t a single feature Coleran hasn’t had a dramatic impact on — from Flow’s look to its architecture. “When Mark came on board, we had some really interesting technology, but we didn’t have the full user interaction model down. The powerful thing with Mark is that although he’d never built software before, his process with what he was doing in film was not that far off. He was trying to match with the story, obviously, but also he would think about what that technology might be used for, and what it might look like. When you look at a specifications document that’s used to build a product, you’re not going through a dissimilar exercise.”

Figure 3. Flow’s interface is both futuristic and familiar. The program’s Real-Time Asset Tracking System automatically records the relationships between pictures, movies, audio clips, fonts, plug-ins, and color swatches. Steve Forde says, “We’re showing the user how things are interrelated. You could have a thousand things going into a Quark or an InDesign document, but you still have to keep that center of reference.” The program’s column view shows asset relationships in a left-to-right flow. Click on the image to see a larger version.

Coleran designs and produces most of his film work in Illustrator and Photoshop; the screens are usually played back on set, so the actors have something to work with. When crafting computer screens for a movie, Coleran generally meets with a production designer to discuss the movie’s setting, as well as its tone and overall look; then he designs screens that meet the specific demands of the script. In many movies and TV shows, what happens on characters’ computer screens is as important to the story as what happens in their conversations — so even the screens in films set in the modern day are often, by necessity, a bit different from what we see when we turn work on our computers. (For one thing, our real-world computer screens still just don’t do very much.)

Figure 4. Coleran’s work appears in the “Bourne” series of action movies; this screen was in “The Bourne Identity.” Coleran says he’s proud of all the films he’s worked on, but he especially enjoyed working on the Bourne films: “We actually managed to do a very realistic and almost plausible sort of look and feel.” Click on the image to see a larger version.

Of course, Coleran knew that creating a user interface for the real world would be at least in some ways much different from creating one for the fictional world of a movie: “The brief itself isn’t so much different, but the thought that has to go into it is so much more. Because you’re not talking about something that’s going to be seen for 30 seconds and then disappear, and that only has to look like it’s going to work. The amount of thought that has to go into making something work day in and day out for numerous different people and different situations is a complex process.”

He adds, “The primary thing with the film stuff is you have to develop the look and feel and style of it. Ninety percent of the work goes into that. With software, a lot more of the work is more about the principles behind it — how it’s going to work comes first. It’s 180 degrees, really.” Both Forde and Coleran believe that Coleran’s nontraditional design background allowed the Flow team to come up with some different sorts of solutions. This project allowed not only Coleran but also GridIron’s engineers to try new things.

Figure 5. Coleran created this screen for “The Bourne Identity.” “It’s a very common criticism of ‘CSI’ and ’24’ and those kind of programs that what [visual designers] do is very unrealistic,” says Coleran. “But they have to do so much in such a short space of time — it’s generally production constraints that make things work not as well as they could.” Click on the image to see a larger version.

One challenging aspect of designing a new kind of interface is knowing which conventions shouldn’t be busted. “Stylistically, you do have to restrain it a little bit and kind of work within the norms and conventions that people are used to,” says Coleran, who explains that the Flow development team wants the app to be completely cross-platform, and to incorporate elements of Mac OS and Windows in one interface, for “the best of both worlds and then a little bit on top as well.”

Figure 6. Flow looks — and functions — like the flowchart app of tomorrow. The program promises to make it easy to revert to a previously saved version of a file, and will then show you how the change will impact your project — for instance, highlighting files that need to be updated. Flow is slated for release in summer 2008. Click on the image to see a larger version.

In the development process, of course, some of Coleran’s more inventive ideas had to be scrapped for the sake of usability — but unlike the video screens in a movie, Flow is a project that will, Forde hopes, continue to evolve. “There’s obviously stuff that happens where you have to move on,” Forde says. “But it doesn’t mean that those things are completely closed. We have a roadmap for 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 — which is great.”

“I see so much potential for Flow,” says Coleran. “Even if I stepped back to doing film work in the future, I know that doing that kind of work is going to be easier because of it.”

Charles Purdy is a former managing editor of Macworld magazine and the author of the book Urban Etiquette(Council Oak Books, 2004).

This article was last modified on January 18, 2023

This article was first published on March 12, 2008

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How Machine Learning Is Winning the Photographic Face Race

Several years ago, some photo applications started to include face recognition f...

Intelligently Resize Images with iResizer

Content Aware Scale, which allows you to resize photos disproportionally without...

Special Offer on JixiPix Photoshop Plug-ins

Press release JixiPix Software has released the availability of a whole new powe...