Heavy Metal Madness: The Art of Labor Day, or is it Leisure Day?

I enjoy a three-day weekend as much as anybody, but Labor Day has always struck me as the most under-celebrated official American holiday. On Memorial Day we temper our long-weekend euphoria with at least a few somber images of Arlington Cemetery in the newspaper and on TV news. On Veteran’s Day, parades are held around the country honoring those who served our country. And you can’t help but conjure up images of Martin Luther King on his holiday, and former Commanders in Chief on President’s Day. But Labor Day? That seems a little vague, and in modern times downright uneventful.

Of course it wasn’t always that way. This young country was rapidly built on the backs of laborers, and the 8-hour workdays, medical benefits, and regulated working conditions we enjoy today came at a high price.

Workers’ struggles are not unique to America by any stretch, but our reasonably free society allowed for bolder expression from laborers wanting to organize and demand more rights. And while it is a gross oversimplification to refer to artists and graphic designers as “sympathetic to liberal causes,” there are more examples of pro-bono artistic expression around the struggles of American labor than almost any other social issue.

Artist Isadore Posoff made this stunning miner for Pennsylvania, the mining capital of America at the time, 1937. Mine workers were among the first to organize, pushing for much-needed safety reforms.

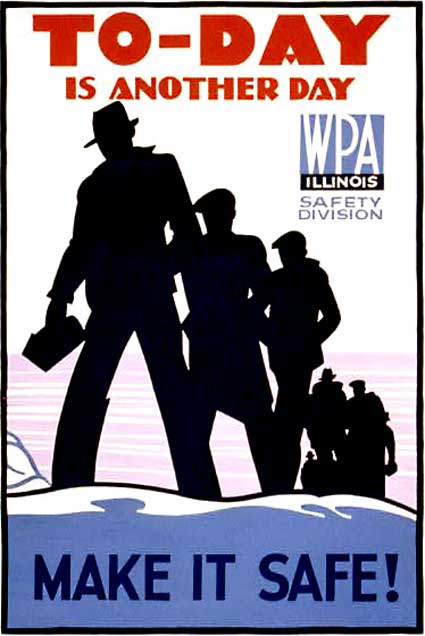

An unrecorded artist created this 1937 WPA poster that promoted safety in the workplace. Thanks in part to the efforts of artists in the WPA program, attention was drawn to work conditions and worker safety. These posters directly lead to many of the workplace safety posters we still see today. (More on the WPA later in this article.)

Workers Begin to Unite

In the United States, most people think of the labor movement as coming into its own in the “Gilded Age” after the Civil War, when moguls and tycoons combined their ambitions with the tools of the Industrial Revolution. But as early as 1806 there was a strike among cordwainers (I looked it up-they’re shoemakers) in Philadelphia for higher wages. That time period also established our government’s strong anti-union policies, which held for many decades to come.

Produced by the United States War Production Board in 1942, this poster of the proud welder was designed to serve as a reminder that our Fascist enemies were using slave labor in their war effort. During World War I and World War II, the U.S. government made every effort to associate hard work with freedom and democracy, rather than a struggle against capitalistic business owners.

Then, between 1825 and 1835, Boston carpenters struck for the establishment of a 10-hour workday, and children in the silk mills of New Jersey went on strike for the 11-hour, 6-day work week. But it was 1877 that marked the bloodiest year in labor vs. government and indirectly led to the establishment of a national holiday honoring labor.

In that year in June, ten coal-mining activists were hanged in Pennsylvania, and in July railroad workers held a general strike that shut down the movement of U.S. mail. As a result, 30 workers were killed and more than 100 wounded in Chicago when federal militia were sent in.

The float from the Women’s Auxilliary Typographical Union in a New York Labor Day parade of 1909. I cropped out the police marching next to the float — they were a regular part of many early Labor Day celebrations, which sometimes erupted in violence.

Labor Day as an Alternative

In every country today except Canada, the United States, and South Africa, May 1 is the day the struggles and contributions of workers are celebrated. And so it was in America until that day became associated with Socialism and Communism.

This 1917 poster issued by the National Industrial Conservation Movement implied that any effort from labor to better working conditions or worker rights was both disloyal, and un-American.

After a number of suggestions from labor leaders for the establishment of a unique American “labor day” celebration, Grover Cleveland, a strong anti-labor president (who was seeking re-election and needed the union vote) agreed to a law establishing September 5th as Labor Day. This concession seemed motivated by a desire to distance American workers from the leftist political leanings of May Day celebrators worldwide, and to wrestle control away from workers and put it in the hands of government.

As late as 1932, many workers were still celebrating May 1 as the day of labor struggles, despite the government’s efforts to shift emphasis to the 5th of September. The association between May 1 and socialism was uncomfortable for both unions and governments.

Cleveland lost the election, but Labor Day was born nonetheless, and in 1898 the head of the American Federation of Labor, Samuel Gompers, described the holiday as “the day for which the toilers in past centuries looked forward, when their rights and their wrongs would be discussed…that the workers of our day may not only lay down their tools of labor for a holiday, but upon which they may touch shoulders in marching phalanx and feel the stronger for it.”

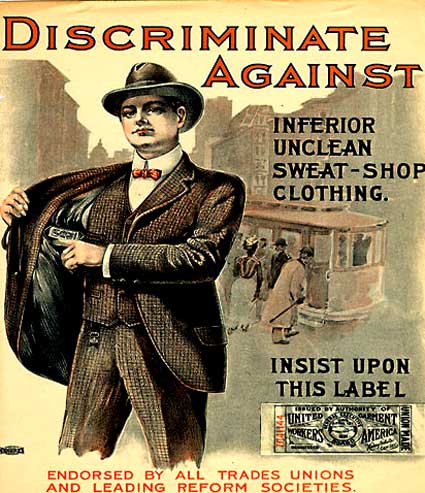

This ad, published in the Saturday Evening Post, March 8, 1902, was an early effort on behalf of unions to promote organized labor as a consumer benefit. Despite many Americans being members, unions suffered from a public relations problem at the turn of the century.

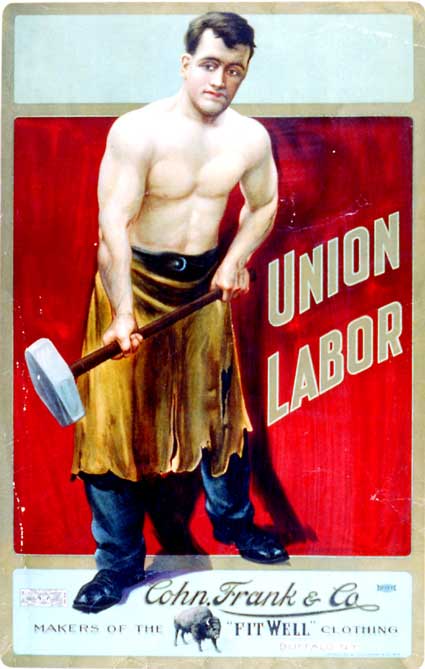

Another example, from 1905, of cooperation between a manufacturer (Cohn, Frank Co. in Buffalo New York) and union to promote the benefits of buying union-made products. It was critical that unions put forth an image of strong, hard-working Americans concerned with quality and value.

Sounds good, but it took many years for the holiday to be accepted by the states, and for years some workers were fined or fired if they took the day off. America’s labor conflicts were really just beginning, and true reform wouldn’t take place until the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. Yet for a few years at the end of the nineteenth century, Labor Day was celebrated with parades and civic recognition of the contribution made by industrial workers.

Did Someone Say, “Holiday”?

It didn’t take long for tired workers (who were still putting in ten-hour days in most places) to view the Labor Day holiday as a time to rest, not to rally. By 1900 many unions were levying fines on members who refused to show up for parades, and prizes were instituted for the locals that had the best turnout. So much for solidarity.

And on it went until the economic crash of 1929 put many workers on the street and at odds with employers even more than before. Low wages became even lower wages, or no wages at all. So in 1930 Labor Day picked up again, and workers united to express solidarity. More strikes ensued, and the labor movement gained momentum throughout the ten-year Depression. This was also the time of the Works Progress Administration and the terrific support of artists that ensued. Many of the best posters and graphics come from the period of 1935 to 1940.

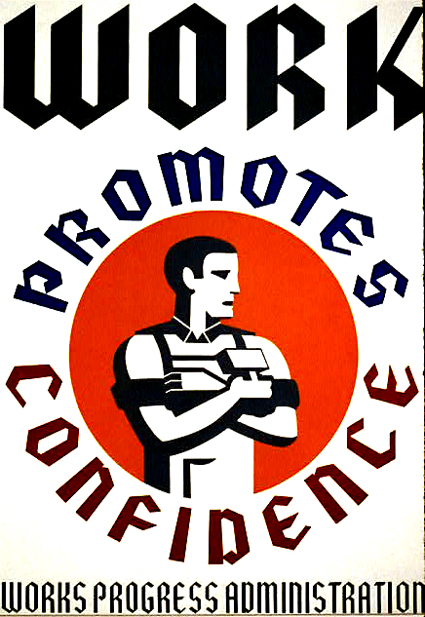

From approximately 1936 to 1941, the Works Progress Administration sponsored artists to create posters, murals, and other works that reflected American life. Sadly, most of the works remain without specific credit, as in this effort from the Ohio Federal Art Project.

By 1950, more than half of Americans belonged to a union. So Labor Day had some teeth to it.

But changes in industry, the economy, and government put pressure on unions throughout the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. The idea of a working class became less definable as many manufacturing jobs turned into service jobs. The word “labor” once had a face to it. Now we say “blue collar” or “white collar” and the managers often outnumber the workers. Most Americans probably don’t know whether they should be celebrating Labor Day. Even for union members, the “labor” moniker has taken on a somewhat dinosaur status.

This WPA poster from 1937 was meant to encourage workers to consider new trades, and was designed by Peter Radin. In this case the WPA was promoting the “industrial arts,” which at the time included pressmen, cabinet makers, electricians, draftsmen, compositors, and radio repairmen, among others.

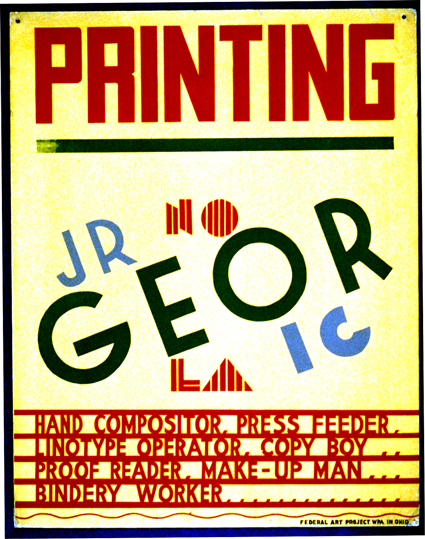

WPA poster promoting the printing arts, which included the titles hand compositor, press feeder, linotype operator, copy boy, proofreader, make-up man, and bindery worker. The jumbled type is a particular favorite of mine.

Birth of the Three-Day Weekend

The real nail-in-the-coffin for Labor Day as anything more than a day off came with the Uniform Holiday Act passed by Congress in 1968. This act established that beginning in 1971, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Veterans Day, and Washington’s Birthday (which was later changed to “Presidents’ Day”), would henceforth fall on the Monday closest to the original holiday date. There was even serious talk of changing Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July to Monday holidays (presumably with a name change for the latter).

Artist Blanche Anish produced this WPA poster in 1937 to encourage men to become airplane mechanics, a relatively new field. The small print lists factory worker, airport worker, aero rigger mechanic, and airplane mechanic as career choices.

One of the sponsors of the bill, Congressman Robert McClory of Illinois, speculated that families would spend the long weekends visiting cemeteries and “famed battlegrounds and monuments.” And New York Democrat Samuel Stratton was quoted as saying that three-day weekends would “refresh and restore the spirits and the energies” of federal and state employees.

Many WPA posters focused on safety and cleanliness in the work place. This 1936 artwork is from the Pennsylvania Federal Art Project. Artist unknown.

But not everyone favored the idea. Democrat from North Carolina Basil Whitener suggested that “a few business organizations would make more profit on Mondays” at the expense of “the tradition and background of our nation. Let us not peg everything to the dollar.”

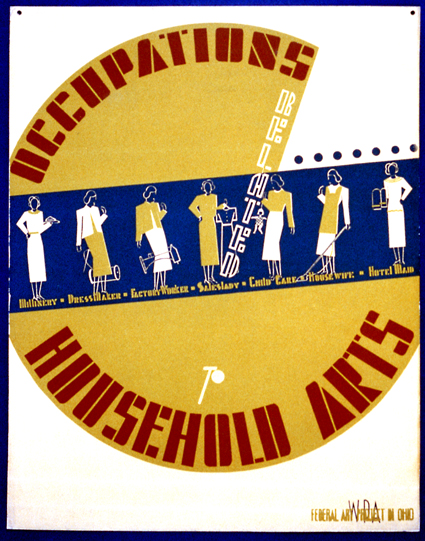

This WPA poster by artist Peter Radin focuses on the “household arts,” which include millinery, dress maker, factory worker, sales lady, child care, housewife (an early recognition of that being a real job), and hotel maid.

The bill was even mocked openly by several Senators and Congressmen. Bills were introduced to rename our holidays as “Uniform Holiday No. 1, Uniform Holiday No. 2,” etc. One member of Congress suggested with a straight face that Christmas and New Year’s Day be moved to Mondays as well.

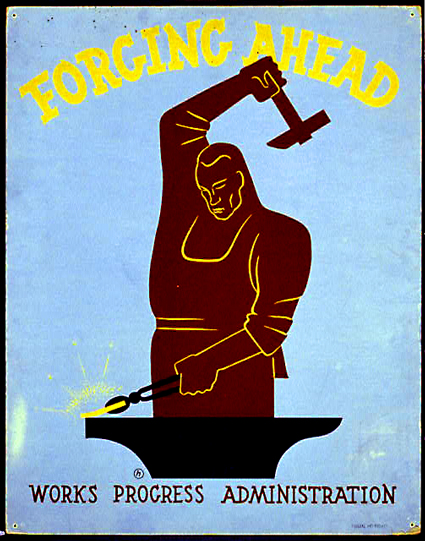

This uncredited WPA poster is a simple statement that both promotes a trade (blacksmithing) and encourages out-of-work Americans to look forward to better times.

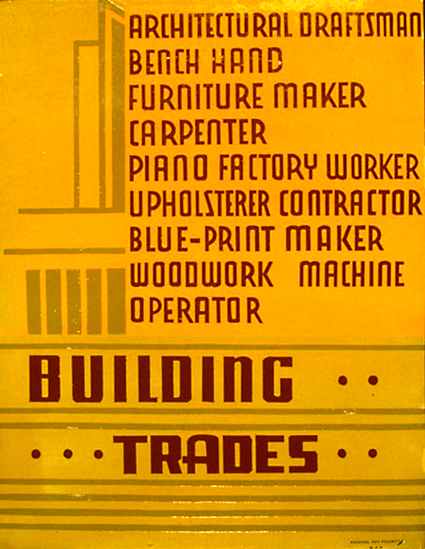

The building trades endured slow times during much of the ten years of Depression in America, but this poster provided good advice. Post-war America went on a building boom of unprecedented scale.

And in a speculation of surprising accuracy, Tennessee Congressman Dan Kuykendall said, “If we do this, 10 years from now our schoolchildren will not know what February 22 means. They will not know or care when George Washington was born. They will know that in the middle of February they will have a 3-day weekend for some reason. This will come.” (I dispute this slightly. Kids today know that President’s Day is a great time to go shopping. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Thomas Jefferson are still brand-name icons, right up there with Colonel Sanders and Martha Stewart.)

But the bill passed anyway, prompting the president of the National Association of Travel Organizers to say, “This is the greatest thing that has happened to the travel industry since the invention of the automobile.” And indeed, according to the AAA, 37.2 million people are expected to travel more than 50 miles from their homes this long weekend.

Robert Muchley drew this image of a man with a riveter in March of 1937. Most of the WPA posters were either made from woodcuts (as is this one) or were silkscreened.

A WPA lithograph from 1936. Artist unknown.

Even though we no longer celebrate labor the way we use to, Labor Day still means plenty of graphic design opportunities. That’s because it’s also one of the biggest shopping days of the year, what with all the summer clearance sales and back-to-school promotions. I guess you could say we’re still celebrating workers, only now they reside at Wal-Mart, Target, and your local gas station, not in an automobile factory or coal mine. And that still makes this a day to recognize the poor working conditions and low pay many Americans struggle with.

A close up of muscular hands by artist Robert Muchley in October 1936. Many labor-related artists focused on the hands. In this case, the WPA poster asked workers to protect their hands, a most valuable asset.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on September 5, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Easily Share Lightroom Photos to a Group

Did you photograph a group event, family gathering, or client shoot and want to...

ShutterSnitch, the Wireless Photo Assistant for iOS

The iPad offers several advantages for photographers. Compared to a laptop, it t...

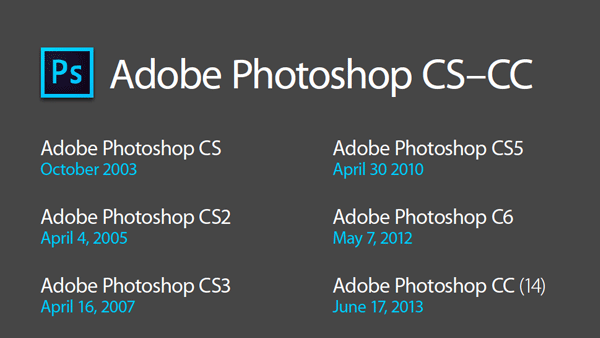

Photoshop New Features Guide

For some time, InDesign users have enjoyed a great free resource that details wh...