Heavy Metal Madness: The Color of Money

When I had a small print and type shop in Monterey California, I rented space from the owner of a car wash, which was next door to me. So it made sense that I would produce various promotions for the car wash in exchange for a reduction in rent, free detailing, or an unlimited supply of pine-tree air fresheners.

One such promotion was a coupon for $5 off a complete wax job, a decent discount for the times. I thought it would be clever to have the “interior” crew at the car wash place the coupons in the car’s visor, with just a portion sticking out. By designing and printing this visible part like a five-dollar bill, I determined that the unsuspecting car owner would pull out of the car wash and later discover this windfall. On close inspection, of course, they would see that it was not a five-dollar bill at all, but a crude marketing piece intended to hoodwink them into a full wax treatment.

I had the cheesiest process camera ever made, a well-worn ATF Chief 20 offset press, and I made my plates by exposing them with photo-flood light bulbs and a pane of glass held down with bricks. Despite these handicaps, the coupons came out pretty well, and I was surprised how convincing they were. Our eye tends to see the image we’re accustomed to, and on casual glance, this piece looked like a folded five-dollar bill. But of course I only printed half of the bill, I put the words NOT NEGOTIABLE in all-caps, used only black ink, replaced the treasury seal with rub-down type, and printed them on light-green laid paper I bought at the printer’s store. Surely no one could confuse these for the real thing.

Figure 1: An innocent promo for a local car wash brought the government knocking on my door.

Even Secret Service Agents Prefer a Clean Car

The Monterey Peninsula is famous for its golf courses, and shortly after launching the $5-off campaign, the U.S. Open Golf Tournament breezed in to town, and along with it various dignitaries, celebrities, and t-shirt salesmen. It was just my luck that ex-president Gerald Ford was one of the luminaries, a long-time golf fan. And though I had voted for Carter, I was pleased that any ex-president would grace our little Peninsula.

Ex-presidents travel with a fairly large Secret Service contingent, however, and during down time I discovered one of the things they do is get their cars washed. Imagine the agents’ surprise when they pulled out of the driveway in a clean car, only to discover my half-witted attempt at fooling people into thinking they had just found a five-dollar bill.

It only took minutes before the Secret Service made the connection between the car-wash coupon and my shop, so they walked over and banged on my door. I don’t think they ever thought I was a real counterfeiter, but as it turns out, I was clearly in violation of the law. They confiscated my original art, my film negatives and the plates. Then they left me with an informative government pamphlet explaining the rules for photographing and printing images of U.S. currency.

Figure 2: It’s in the detail. From the Secret Service Web site, examples of real (left) and counterfeit (right) images.

Here’s the current rules, in case any of your clients are car wash owners:

The Counterfeit Detection Act of 1992 permits color illustrations of U.S. currency provided:

- the illustration is of a size less than three-fourths or more than one and one-half, in linear dimension, of each part of the item illustrated;

- the illustration is one-sided; and

- all negatives, plates, positives, digitized storage medium, graphic files, magnetic medium, optical storage devices, and any other thing used in the making of the illustration that contain an image of the illustration or any part thereof are destroyed and/or deleted or erased after their final use.

It is legal to show money in motion pictures or video, provided prints are not made from those sources (unless they meet the requirements above).

Figure 3: All sorts of reproduction is used for counterfeiting. Here, also from the Secret Service Web site, an authentic currency enlargement (top) and bogus bills printed by (from left to right) monochrome, inkjet, black and white, four-color.

I’m telling you this because I’m probably violating these rules myself again in this article, though with the Web it’s hard to tell, since screen-resolution and servers can affect the size at which images are displayed. And since many of these images came from a royalty-free image CD, I’m guessing the “no storage of the image” rule is not widely enforced.

Printing Money for a Living

In researching the printing of real money, I garnered enough interesting facts and trivia to fill several columns, but I promise to only highlight a few here, and encourage anyone interested to visit the Bureau of Engraving and Printing Web site. And if you live in or visit either Washington, D.C, or Fort Worth, Texas, I encourage you to take a tour and witness the 65-step art of currency manufacturing. The BEP prints approximately 37 million currency notes each day with a face value of about $700 million (almost half are one-dollar bills).

Figure 4: The Fort Worth, Texas plant of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, opened in 1991. There are only two facilities in the United States for printing money.

Printing and design methods for currency vary around the world — some countries print offset, some design using computers, and some are experimenting with embedded electronics. But in the United States, the printing methods for money have gotten faster and more efficient, but the core techniques have not really changed much since 1877 when all printing was taken over by the BEP.

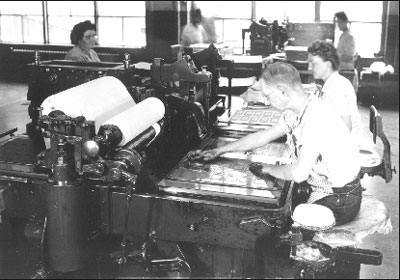

U. S. currency is still printed using the intaglio, or gravure method. In this process, images are etched (recessed) into chromium-coated plates that are then mounted on a sheet-fed rotary press. The intaglio process consists of three pretty simple steps. First, ink is applied to the plate, where it sinks into the recesses. Then, a blade wipes the plate clean, leaving only the ink in the recesses. Thirdly, nearly 20 tons of pressure is applied to press the plate against the paper (that’s why money is so flat) and the ink is squeezed out and on to the paper.

Figure 5: The first presses used by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing were steam-powered Milligan presses. Here, in the 1930s four workers per machine use a more modern sheet-fed intaglio press made for the government by R. Hoe & Company. Much of the work was still done by hand. Modern presses are more automated and require fewer operators. The women who fed the press were called “putter-on-ers,” and the ones who took the sheet off at the end were called “taker-offers.” The inker was always a man.

Intaglio printing allows for very fine details, and is interesting more from a pre-press perspective, than from the actual press, which looks like any number of other presses. And though you can, by using film, etch an intaglio plate from a digital or printed image, the United State has chosen to stick with traditional engraving for producing our money.

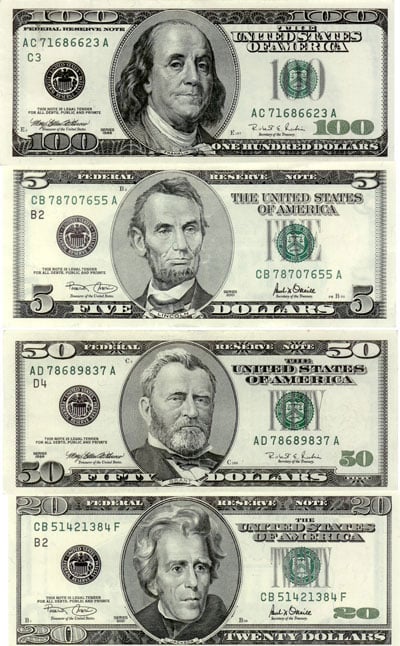

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing employs about a dozen engravers, who etch all those tiny lines, type and dots out of metal at actual size and using traditional hand-tools. Usually the engravers work from a drawing or a photograph, and it can take up to 500 hours of painstaking work to produce a presidential portrait. The good news is that these original engravings have a very long life span — the old Lincoln portrait on the $5 bill was done in 1869 and used until its recent makeover.

Figure 6: Here, master BEP engraver Tom Hipschen works on a portrait of Ronald Reagan. The engravers also prepare stamps, White House invitations, and other fine documents.

Various parts of a bill are etched separately from one another — usually by multiple engravers — one doing type, one images, and another doing the fancy borders. These pieces are then welded together in the right configuration and a single original is created. In a process known as siderography (which involves making a soft transfer medium) the original engraving can be duplicated. These dupes are then imposed into sheets and press plates are made from them. It is surprising how little detail is lost in these steps.

Figure 7: When the images were enlarged on our currency, new etchings had to be done — some taking up to 500 hours. The images were offset from the center to prevent folding damage to our presidents.

Not all of a bill is printed by this method. Things like the serial numbers and some of the seals are over-printed using letterpress techniques. Most of the modern anti-counterfeiting measures have to do with ink formulations (like adding metal flakes to cause a change of colors depending on the light), or with adding of very fine detail (which is difficult to reproduce with toner-based copiers). Take a look at one of the newly designed bills under a loupe, and imagine hand-carving that detail into metal.

All U. S. money is sheet-fed printed with paper manufactured by Crane and Company, containing 25% linen and 75% cotton. A brief experiment was done by the BEP in 1991 to print using roll-fed web presses, but that turned out not to be practical. The green ink was originally chosen because the pigment was readily available and it stood up better in use.

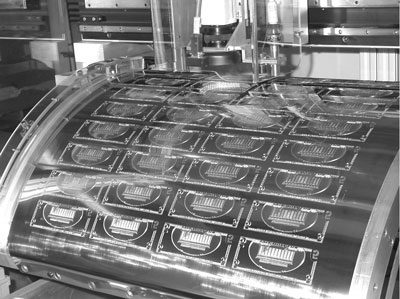

Figure 8: An imposed plate of five-dollar bills on press.

What’s in Your Wallet?

The history of money is the history of the world — full of surprises, at least to me.

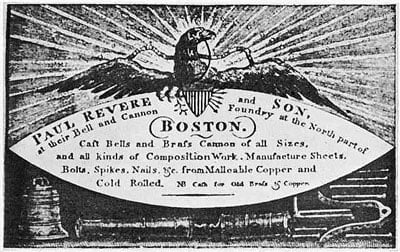

Paul Revere we know was a silversmith, but he also engraved the first plates for early colonial bank notes. And of course Benjamin Franklin was an early proponent of paper money, in part because he got the government contract to print it in his shop. One story has Franklin deliberately misspelling Pennsylvania on a note printing in the hopes that counterfeiters would correct the mistake and thereby give themselves away.

Figure 9: Paul Revere’s business card. He was not only a skilled silversmith, but is considered the “father” of the engraved bank-note industry in America.

Abraham Lincoln created the Secret Service to investigate and stop counterfeiting, which was particularly rampant after the Civil War. It was later that the Secret Service became the protector of the president. Too bad for Lincoln, who signed the order creating the Secret Service on the day he was shot to death at Ford Theater.

The phrase “to pay through the nose” comes from Danes in Ireland who slit the noses of those who were behind in their taxes.

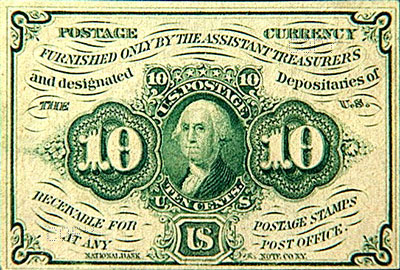

Figure 10: The smallest bill produced in the US was a 5 cent note, and the largest was a 100,000 bill with Woodrow Wilson on the face. Here is an early 10-cent note with Washington’s image.

A typical one-dollar bill lasts only 22 months in circulation, and can withstand 4,000 double folds (forward and then backwards) before it will tear. A $100 bill (the largest currently in circulation) lasts nearly 8.5 years. Not in my wallet.

The Secret Service drive large, darkly-colored Chevrolets, and according to my neighbors at the car wash, they didn’t leave a tip.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on May 6, 2004