A New Kind of Camera

If you’ve even dabbled in digital photography, you probably know that digital cameras fall into two main categories: point and shoots, and SLRs. Typically, point and shoots are smaller than SLRs, with lenses that don’t come off, and you preview your shot through an LCD on the back of the camera. SLRs have removable lenses and, via a system of mirrors and prisms, you see your shot through the same lens that exposes the sensor. Also, SLRs have bigger image sensors, which can yield better image quality and less image noise.

When deciding between these two classes of cameras, you’re usually forced to weigh some tricky issues: Is small size more important? Or better quality? Do you need more artistic flexibility? What about performance in low light?

But now there’s an alternative: mirrorless cameras with removable lenses. These cameras use a sensor that’s bigger than a point-and-shoot’s, but smaller than an SLR’s. They have interchangeable lenses like an SLR, but because they don’t have the mirrors and prisms that let you look through the lenses, the camera bodies and lenses can be much smaller than an SLR. In other words, these cameras fit perfectly between point-and-shoot and SLR cameras.

The most popular and prevalent cameras in this new category are those that conform to the Micro Four Thirds standard, a specification developed by a consortium of camera companies, chief among them Olympus and Panasonic.

If you’re an SLR shooter who’s been contemplating a second, smaller camera but haven’t wanted to give up the advantages of an SLR, or if you’re a point-and-shoot user who’s ready to move on to a camera with better image quality but you don’t want to commit to the bulk of an SLR, a Micro Four Thirds camera might be exactly what you’re looking for.

After reading this article, you’ll better understand the trade-offs and benefits of a Micro Four Thirds camera.

A Little History

In 2002, Olympus and Kodak “agreed to implement the Four Thirds System (4/3 System), a new standard for next-generation digital SLR camera systems that will ensure interchangeable lens mount compatibility.” Their goal was to define a standard that would attract many camera vendors and create a large assortment of lenses that would fit all the new cameras.

The standard promised to yield lenses that were smaller and lighter than those on typical SLRs. The Four Thirds system also promised better image quality thanks to an image sensor that’s smaller than SLRs’ APS or 35mm sensors, yet directs light more efficiently due to microlenses that cover individual pixels in the sensor. (For more detailed technical specs, see the Micro Four Thirds Wikipedia entry.)

A comparison of sensor sizes.

The Four Thirds system only partially fulfilled this promise. For example, while Olympus’s first Four Thirds camera, the E1, was extremely well made, it was hardly small. Four Thirds cameras have grown smaller since then, but so have SLRs. Four Thirds cameras are smaller and lighter than most SLRs, but the difference isn’t enormous.

And despite the fact that Four Thirds systems were engineered from the ground up for digital imaging, they’ve never shown an image quality advantage over regular SLRs. An SLR’s larger image sensor translates into better dynamic range and less noise.

Finally, Kodak never released a Four Thirds camera. Instead, Panasonic joined Olympus and, so far, they’re the only companies producing Four Thirds cameras.

To address the size issue, a sub-set of the Four Thirds standard was created. Panasonic released the first Micro Four Thirds camera, the LUMIX DMC-G1, in October 2008.

Panasonic’s LUMIX DMC-G1.

With several Micro Four Thirds cameras on the market now, the new standard is proving to be the perfect choice for some photographers because it offers quality that’s near SLRs in a size that’s near-point-and-shoot cameras.

The View from the Camera

Because the Micro Four Thirds spec states that the lens has to be a certain distance from the sensor, there’s no room inside the camera for a mirror behind the lens. This means it’s impossible for these cameras to have an SLR-like viewfinder. Instead, you’ll always use the camera’s LCD screen as a viewfinder (also called a “live view” and “live preview”).

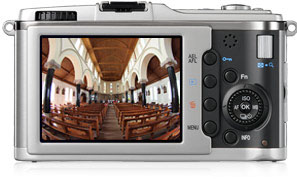

The Olympus E-P1‘s LCD screen.

I’m not crazy about LCD viewfinders. I much prefer blocking out the world with the camera to concentrate on my composition, and I like the extra stability I get when I’m mashing the camera up to my face. While modern LCDs are much better than their predecessors, offering excellent color and detail, none are easy to use in bright daylight.

What I find particularly annoying about LCD viewfinders is that they don’t show you the complete dynamic range of your scene. Shadowy areas tend to go completely black in an LCD viewfinder, so if you’re trying to compose with forms that are in those shadows, you won’t be able to see them. You can look back at the scene with your eyes, but that slows down the shooting process and can be distracting.

Because it’s harder to hold a live view camera steady, I find that very precise composition — i.e., shots where I’m very concerned about the edges of the frame — take much more time and effort to compose.

That said, I have gotten faster with the LCD viewfinders on Micro Four Thirds cameras during the time I’ve been working with them. They’re still no substitute for an optical viewfinder, but they’re not the total deal-breakers I once thought they were.

There’s nothing in the Micro Four Thirds specification that forbids an optical viewfinder of some kind. However, in an interchangeable lens system, optical viewfinders become more complicated, because there’s no way to add a viewfinder that will work with every lens that you might attach. Olympus offers an optional optical viewfinder for its 17mm lens. It clips into the camera’s hot shoe and provides a reasonable facsimile of the coverage supplied by the lens. However, it’s still not a completely accurate view of the final image, and it’s not compatible with any other lenses.

The Olympus VF-1 optical viewfinder for the PEN E-P1 Micro Four Thirds digital camera.

For the E-PL1, Olympus offers a clip-on electronic viewfinder. Because it works with any lens, and because it offers excellent image quality, it’s a darn good substitute for a true, through-the-lens optical viewfinder. It’s still not as good as what you’ll find on an SLR, but for shooting in bright daylight, it can mean the difference between getting and missing a shot.

Panasonic also sells an electronic clip-on viewfinder that works with any lens, but its quality is only mediocre. However, since Panasonic provides a much better screen on the back of the camera than Olympus does, viewfinder quality is a trade-off at this point. If you want a great screen on the camera, Panasonic has the lead, while if you want a very good clip-on viewfinder, Olympus comes out in front.

The Panasonic DWM-LVF1 electronic viewfinder can pivot.

These issues are most likely not going to change in future cameras. In short, there’s no substitute for an SLR viewfinder, so if you’re switching to a Micro Four Thirds camera from an SLR, you’ll always face a viewfinder compromise. You’ll have to try out one of the cameras to decide whether it’s a deal-breaker for you.

Image Quality

Camera marketers try to sum up image quality with a single parameter: pixel count. But savvy photographers understand that higher pixel counts don’t necessarily mean better image quality. As pixel density increases, so does noise, so good image quality requires a balance of megapixels and low noise.

Twelve to thirteen megapixels is enough to produce a good 13″ x 19″ print, and with a little work you can even produce good larger prints — larger than you could achieve with 35mm film. If Micro Four Thirds vendors continue to take this reasonable approach to pixel count — rather than cramming in dozens of pixels — then we should continue to see cameras that yield image quality similar to the Olympus E-P1 and Panasonic’s DMC-GF1.

Both of these cameras offer excellent dynamic range and detail, and they yield great images all the way up to ISO 1600. While their low light/high ISO performance is not as good as what you might find from a high-end SLR, it’s certainly better than what you’ll get from a point-and-shoot camera. SLR shooters won’t feel a tremendous compromise when using one of these cameras, while point-and-shooters will find a whole new world of subject matter opening up, as they realize that they can shoot effectively in low light.

Depth of field — the area of an image that’s in focus — is partly a function of sensor size, so as sensor size gets larger, you can shoot shallower depth of field. If you’re an SLR shooter who’s used to being able to capture very shallow depth of field, then you’ll be giving up some depth of field latitude. However, if you’re a point-and-shoot user, you’ll be gaining the ability to blur out backgrounds to a far greater degree than you ever could with a point-and-shoot camera.

Lens Selection

One thing that you won’t have to compromise on if you’re coming to Micro Four Thirds from an SLR is lens selection. Between Olympus and Panasonic, there’s an excellent selection of high-quality micro four thirds lenses available now. While you won’t find tilt/shift lenses on Micro Four Thirds cameras, you can get something that’s not available for SLR cameras. Both Olympus and Panasonic sell nice “pancake” lenses — extremely small fixed focus lenses that are ideal for street shooting on a small camera. In other words, both vendors are being smart about creating lenses that are useful for a compact, high-quality camera.

And in addition to lenses engineered specifically for Micro Four Thirds cameras, there’s also a huge assortment of adapters that let you use other types of lenses. For example, you can adapt to use the entire range of Four Thirds lenses, but you can also adapt to use everything from Leica R lenses to Pentax K-series lenses, to lenses from film movie cameras.

While some of these lenses will be somewhat silly on a Micro Four Thirds camera simply because of their size, others will be a very good fit, and if you already own a nice lens collection, the adapters make these cameras even more attractive.

Price

Price is almost always a factor when you’re choosing cameras, of course. The Olympus E-PL1 and Panasonic DMC-G10 micro four-thirds cameras are around $550, and the Panasonic Lumix DMC-GF1 with 14-45mm f/3.5-5.6 lens is a bit over $700.

By comparison, the new Canon PowerShot S95, a good point-and-shoot, is about $400. You can find enthusiast-level SLRs in the $500 to $700 range; for example, the Nikon D3000 with kit lens is about $550, and the Canon EOS Rebel T1i with kit lens is about $700.

Do You Need One?

I’ve been shooting almost exclusively with an SLR for years. While I own a couple of point-and-shoots, for any kind of serious shooting, I always take my SLR, for its better high-ISO performance, better overall image quality, shallower depth of field ability, and speedier handling.

Micro Four Thirds cameras are the first usable SLR alternative for serious shooting. There’s very little image quality penalty, the depth of field compromise is small, and they really can fit in a coat pocket, making them easier to carry than an SLR. Best of all, they can hang on your shoulder all day long without giving you a pain in the neck.

Both Samsung and Sony now offer their own mirrorless, interchangeable lens cameras, but they’ve struck out on their own, rather than conforming to the Micro Four Thirds standard, which means they have a much smaller lens selection than what you’ll find with cameras that do adhere to the spec.

For the point-and-shoot user who wants to move into a world of better shooting, but who just can’t handle SLR bulk, a Micro Four Thirds camera is an excellent option.

Hi, Ben:

Thanks for this informative coverage of this new (to me, anyway) format.

I’ve always felt that a camera that gets left home because it’s uncomfortable can never capture that important unexpected moment.

I wanted to point out something about noise that I didn’t see in your article, not the unruly image pixels, but the mechanical sounds of flippin’ mirrors.

Just imagine if working press pool photographers used mirrorless digital cameras (or rangefinder-model Leicas) – the actual event wouldn’t be nearly drowned-out by shutter clatter. There are many situations where camera noise is intrusive, annoying, and disturbing to folks who happen to be in the space where a photographer wants to shoot.

As to the trade-off between mirror-prism systems vs. mirrorless, there was a 35mm SLR camera in the ’60s or ’70s that used a non-moving “half-silvered” optical element in the image path to divert part of the lens’s image to a viewing screen, and part to the film plane. I think something moved across the view screen or eyepiece to block non-image-forming light during the moment of exposure; this may have made a noise, but one much quieter than a moving mirror.

Regards,

___________________

Peter Gold

KnowHow ProServices

Hi, Ben:

Thanks for this informative coverage of this new (to me, anyway) format.

I’ve always felt that an uncomfortable camera that’s left home was inferior to one that’s so comfortable it’s always with me, because it can never capture the unexpected photographic moments that make my pictures worth taking and looking at.

I wanted to point out something about noise that I didn’t see in your article, not the unruly image pixels, but the mechanical sounds of flippin’ mirrors.

Just imagine if working press pool photographers used mirrorless digital cameras (or rangefinder-model Leicas) – the actual event wouldn’t be nearly drowned-out by waves of shutter clatter. There are many situations where camera noise is intrusive, annoying, and disturbing to folks who happen to be in the space where a photographer wants to shoot, not to overlook losing a subject’s spontaneity that makes many photographs so compelling.

As to the trade-off between mirror-prism systems vs. mirrorless, there was a 35mm SLR camera in the ’60s or ’70s that used a non-moving “half-silvered” optical element in the image path to divert part of the lens’s image to a viewing screen, and part to the film plane. I think something moved across the view screen or eyepiece to block non-image-forming light during the moment of exposure; this may have made a noise, but one much quieter than a moving mirror. As I recall, the extra weight of the solid optical-glass image-splitting prism, its cost, and lost light-efficiency, combined to kill the product. Perhaps modern technology can solve those shortcomings.

Although off-axis optical viewfinders, either built-in or add-on, may be useful to show a lens’s angle of coverage – even show out-of-frame area to help anticipate action coming into frame – their offset from the lens’ angle of view isn’t acceptable to some photographers who need precise placement of elements in their subjects.

Regards,

___________________

Peter Gold

KnowHow ProServices

I don’t know if I am posting this in the right place, but as a longtime CreativePro subscriber, I figured I might as well ask my questions here.

To start with, I’m an old graphic design geezer (actually not THAT old) and will be retiring soon. I had always planned to do oil and watercolor paintings when I retired, but I developed a neurological condition a couple of years ago (hand tremors) that makes painting difficult now. So I’ve been thinking I might to get back into photography instead, to satisfy my creative bent.

So, I have two questions:

(1) II have a couple of really nice, but older, SLR lenses I used to use on my old Olympus film camera. Do you know whether older SLR lenses will fit on any of the newer cameras on the market?

(2) What type of new camera would you suggest for someone with shaky hands?

Thanks in advance for your help.

Hi Ovelky,

You can get adapters for using older lenses on new cameras, but you have to read the fine print pretty carefully. You probably won’t get autofocus, and you may lose lose a stop or so, because of the adapter. So, in general, you’re gonna have an easier time and less hassle by – sorry – investing in new lenses.

As for shaking hands, stabilization might be just the answer. Whether you opt for stabilized lenses, or a stabilized sensor, if your shaking isn’t too bad, stabilization technology might be able to smooth it all out.

Camera-based stabilization doesn’t show in the viewfinder, so if you tend to shoot a lot of telephoto, you might want to go with lens-based stabilization, as it will make framing easier.

Good luck!

–Ben