Scanning Around With Gene: Listening to Music with Both Ears

I recently splurged and used ten years’ worth of American Express points on a pair of Etymotic headphones for my iPod. If you aren’t familiar with Etymotic, all I can say is start saving now. After countless stereo systems and several music formats, I thought I was finished being wowed by music. But listening with the iPod/Etymotic combination is like the first time you heard “Dark Side of The Moon” in stereo while stoned, only you can do it on the bus, and you don’t get hungry afterward.

There’s something about stereophonic sound that made graphic designers want to use perspective type, as shown in these examples scanned from record album covers. Twentieth Century Fox used stereo soundtracks first on its Cinemascope films, thus the name “Stereoscope.”

The mind plays great tricks on us, especially when it comes to sound. By comparing volume and other qualities, one set of ears can triangulate sound waves and reconstruct two channels into the impression of a limitless spatial sound environment. We take this for granted now, but it was a technical and artistic challenge for audio engineers to record and reproduce sound in a way that could trick us into hearing things where they weren’t really taking place, like in the middle of our heads.

So you can imagine that when record companies were able to move from monaural (one channel) recordings to binaural (two distinct channels) recordings, it was a big challenge for the marketing department.

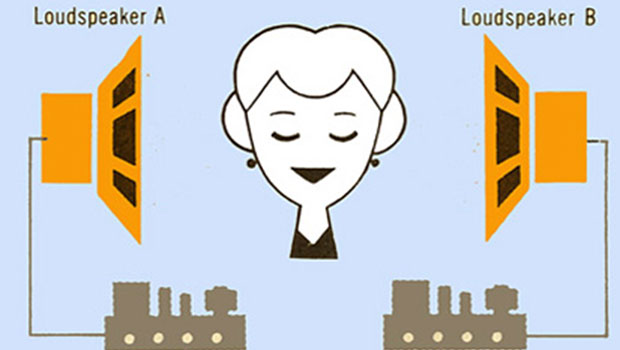

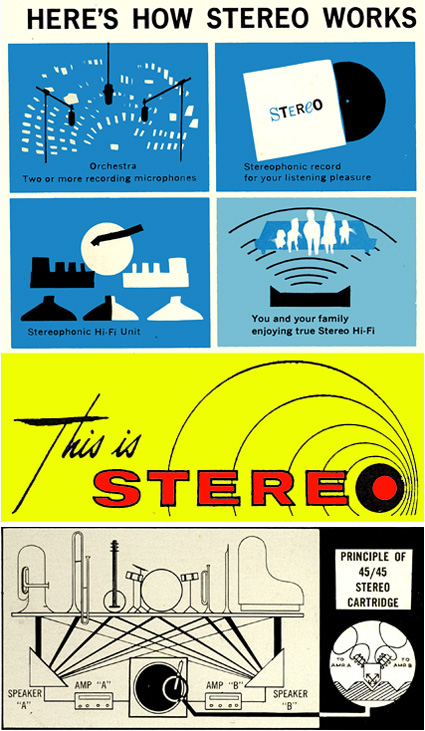

One of the ways to generate interest in stereo was to explain how this “miracle of sound” worked. It was not unusual in the early days of stereophonic recordings to see illustrations such as these from RCA Victor (top) and Mercury Records (bottom).

Suddenly it was possible to bring the orchestra into your living room; with your eyes closed and a little imagination, you could hear the string section on the left and the horn section on the right, with the timpani coming like magic from the middle! Describing and showing this process visually was not an easy task.

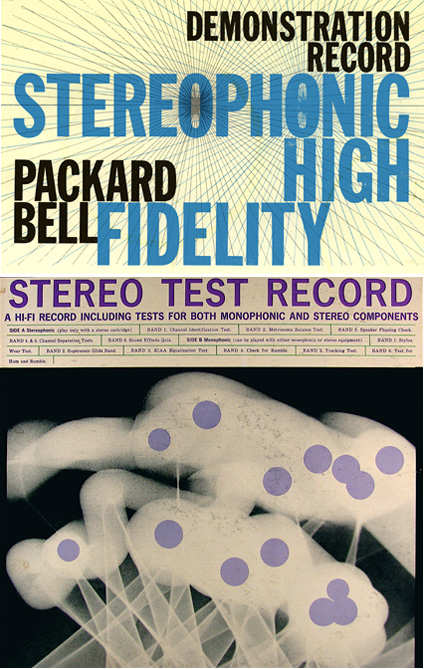

Hearing really was believing when it came to the introduction of stereo. Many record companies and most phonograph manufacturers issued stereo “test records” like these four, all designed to help convince your neighbors that you truly could hear a train go from one side of the room to the other.

The Mandatory History Part

Thomas Edison made the first sound recording on December 6, 1877. (He chose “Mary had a little lamb,” thus missing a perfect opportunity for making it into Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations). He filed for a patent immediately, which was granted a few months later. A lot happened over the next few decades, but a few milestones stand out on the road from that first tinfoil cylinder to the iTunes Music Store and digital-quality stereo sound.

During the Paris Electrical Exhibition of 1881, Clément Ader demonstrated a system whereby people would pick up two telephones connected to a remote live musical performance, hold one to each ear, and experience what Scientific American called a “very curious and … remarkable illusion.” For a brief period in France and England, coin-operated services at hotels and cafes employed this technology, but as it required a live orchestra on the other end of the two phone headsets, it wasn’t practical long-term.

Nearly everyone made some sort of 3D reference to stereo music. This example is from an album titled “Stradivari Strings,” featuring music “for those who dine by candlelight and toast your conversation with champagne.”

The first coin-operated juke box was installed at the Palais Royal Saloon in San Francisco and earned more than $1,000 in the first six months. It wasn’t called a juke box then; it was referred to as a “nickel-in-a-slot” machine.

Verve records featured “Living Sound” (the blue background, top) while Command Records was proud of its recording methods employing 35mm movie film (yellow background, below). The 35mm process gave Command the confidence to claim: “The first time you hear this record will be one of the most startling experiences of your entire life.”

By 1913 the recorded cylinder was largely replaced by the disc format, predecessor to the stereo 33 1/3 RPM record album format. In 1925 the first electrically recorded discs were made using technology developed by Western Electric and Bell Labs. This made it possible to record larger orchestras and bring sound to the movies.

In the early 1930s, Harvey Fletcher (no, not Phil Spector) at Bell Labs created the “wall of sound” concept, which entailed up to eighty microphones placed around an orchestra. Each of these was then tied to a separate loudspeaker placed in the same position as the microphone in another room. And though this produced a very rich sound, not everyone could have 80 loudspeakers in their living room connected by wire to a symphony hall.

In 1931, EMI opened the world’s largest recording studio on London’s Abbey Road, with technology that laid the foundation for stereo recording and playback a few years later.

At first people were a bit confused by the difference between HiFi and stereo, partly because there was also HiFi Stereo. In the beginning, however, “high fidelity” referred only to records recorded on better equipment. There was no set standard to define HiFi, and most early HiFi records were not stereo, though they typically sounded better than previous recording methods.

The term “stereophonic” (from the Greek stereos=”solid” and “phone”=sound) was coined by Western Electric, in part based on the term “stereoscopic,” which was widely used to describe 3D photography of the time. Western Electric first demonstrated stereophonic sound at a meeting of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers in 1937. By then the Brits had already patented a two-channel recording and playback method which, 25 years later, would become a standard for stereo records.

Bell Laboratories gave an historical demonstration on April 9 and 10, 1940, at Carnegie Hall in New York. They set up three large loudspeakers on the stage and played back a previously recorded symphony from the Philadelphia Orchestra. Reports at the time described the audience as “spellbound and a little terrified” of the stereophonic playback, and at least one prominent musical conductor at the demonstration complained that it was “too loud.” So not only was this the first time the public heard stereo music, but it was also the beginning of a battle over volume control that rages in homes to this day.

The idea of so much space and effort devoted to music in the home was new and required people to think of the stereo as the center of at least one room. Proper speaker placement and separation was demonstrated in many illustrations, magazine articles, and pamphlets handed out at music stores.

That same year, Disney released Fantasia, the first motion picture to employ stereo sound (in a process the company called “Fantasound.”) The experiment was not a financial success and for its general release, Disney re-mixed Fantasia with a monaural soundtrack.

Arrows, lightning bolts, fireworks–graphic designers used all sorts of tricks to convey sound that was somehow “alive” and more “dynamic” than before. And sometimes just a stylized version of the word “stereo” had to do the job.

It took the advent of magnetic tape recording (mid-1940s), long-play records (1948), innovations in speaker technology by Paul Klipsch (1945), FM radio (1953), the release of a pioneering record-cutting machine from Westrex in 1957, and a number of other developments to bring stereo to the masses. But by the early ’70s, stereo recordings became the norm.

A Marketing Challenge

Describing the benefits of stereo sound was not easy. It was best sold by demonstration, and even then some people had to be convinced there was enough difference to justify purchasing new playback equipment (including two amplifiers, two sets of speakers, and a new turntable).

Every record company had, at minimum, a logo designed to indicate an album was, indeed, true stereo. These five logos are each from a different label.

The record-buying public was already getting jaded, having been through the format conversion from 78RPM records to 33 1/3 RPM, and the much-touted era of “Hi Fidelity,” which was a somewhat vague term used to describe music with a wider frequency range.

During the transition from mono to stereo, many companies re-packaged earlier work with some form of sound “enhancement,” which some referred to as “simulated stereo.” You had to read the fine print to discover if something was actually recorded in stereo.

In the beginning, the record industry emphasized technology, throwing lots of new terms and specification at the public, hoping to intimidate them into feeling left out of a cutting-edge movement. Record album covers had extensive information about the machines used to record and manufacture the disc, listing stats about frequency response, harmonic distortion, and the like. On an album from Silver Seal Records, buyers are advised that “a maximum stylus velocity consistent with minimum distortion is achieved in the mastering.”

No one knew the definition of “minigroove” or was familiar with the Fairchild #641 Uni-Groove cutting head, but it sounded impressive on the label.

Most record companies came up with names for their recording processes, only some of which were truly unique. That’s why terms like “panorthophonic,” “duophonic,” “radial sound,” “stereoscope,” “ultraphonic,” and “spectra-sound” all described essentially the same thing. With Vanguard Records’ “Stereolab” process, listeners were assured that “the playback, when properly adjusted, will simulate the illusion of an orchestra actually playing in the superb auditorium of the Great Hall in the Musik Verien, in Vienna.” Yes, but what about simulating the Ramones at CBGB’s? Would that be Distort-o-phonic?

Twentieth Century Fox used a number of different versions of the Ultraphonic name and also marketed some records as being recorded in “space-age stereo.”

And on a visual level, graphic designers employed lots of spiraling circles, jutting arrows, and full-color spectrums to convey the message of wide-open sound. Listening to stereo was like looking at a beautiful rainbow over the Grand Canyon. So many colors! So many sounds! So wide! So deep!

What better way to convey a richer and fuller sound experience than to reference the color spectrum? That’s exactly what many record labels did. I wonder if Apple Computer will be sorry they gave up the rainbow-apple logo, now that they’re in the music business.

There were many efforts to explain stereophonic music and to educate the record-buying public on how best to enjoy this exciting new experience in listening pleasure. These included “demonstration” records that employed such hokey tricks as trains passing from one side of your head to the other, and announcers saying “Now you hear me in your left ear,” followed by “Now you hear me in your right ear,” and finally “Now, like magic, you hear me in the center, between both ears!” One album recommended that “in order to enjoy this recording to its fullest, set the volume control at the point at which the sound fills the room and is not objectionably loud.”

Since many early recordings were actually not done very well, the true benefits of stereo were demonstrated with records produced specifically to show off the separation between the channels.

More explanatory drawings from record album covers.

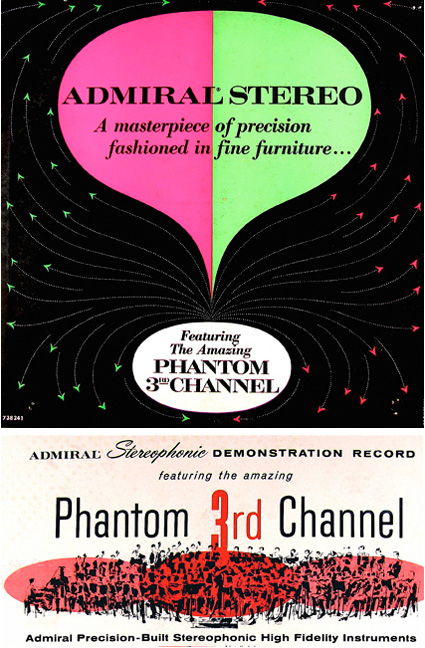

Admiral, in describing its stereophonic equipment, referred to the “phantom third channel” that created “sound so real the live orchestra will suddenly seem to be on stage in front of you.” Westminster Records used terms like “panoramic” and “three-dimensional” and “feeling of presence” to promote its recordings. Mercury Records spoke of its patented “Living Presence” process and threw out references to “breadth” and “depth” and “airy spaciousness” (a term I often use to describe my own work habits).

Admiral referred to the “phantom third channel,” adding a bit of mystery to the already bewildering idea of stereophonic sound. Perhaps they thought people would be more willing to accept a somewhat supernatural explanation as to why it sounded like there was a speaker in the middle.

No Longer Such a Big Deal

Of course, symphony performances gave way to jazz which gave way to rock which gave way to punk which gave way to rap, etc. The idea of being “right there” in the best seat in the house didn’t matter so much. Studio recording moved beyond trying to accurately capture the sound of a live performance into its own art form.

RCA claimed to have revolutionized the music world with its Dynagroove process, which mixed sound so that it reproduced better on low-end equipment. Some audio purists felt the process compromised the music, much like over-sharpening or turning up the saturation in Photoshop compromises an image.

For a few years in the early ’70s, a move was made to promote “quadraphonic” sound, wherein four speakers are used to create an even wider sound. While this technology didn’t take off in the consumer market, it laid the foundation for what we know today as surround sound.

By the end of the ’70s, not only was it taken for granted that modern recordings would be stereo, but we were seeing the end of vinyl records as the format of choice. And while there are still “vinyl heads” out there claiming records sound better than CDs, most of us have moved on and see the benefits of digital music.

Tops Records used the term “ultra-phonic,” Capitol called its process “FDS” (full dimensional sound), and London records had both “ffrr” (full frequency range recording) and “ffss” (full frequency stereo sound). And we thought today’s technology was heavy on the acronyms!

In my next column, I’ll look at stereo system ads from the ’70s and reflect on that coming-of-age experience called “buying your first stereo.” Not only was bigger equated with better, but the typical stereo sales person was a unique breed (with unique hair styles, too).

Come to think of it, aside from the bigger is better part, you might say shopping at a stereo store in 1977 was similar to shopping at an Apple store today: You almost always left spending more than you intended to, but only after the sales person spouted a lot of technical specifications and helped you see why more is always better.

This article was last modified on May 18, 2023

This article was first published on May 12, 2006

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Free 3D Photoshop Objects from Pixelsquid

Online image libraries come and go, and the good ones get swallowed up by Getty....

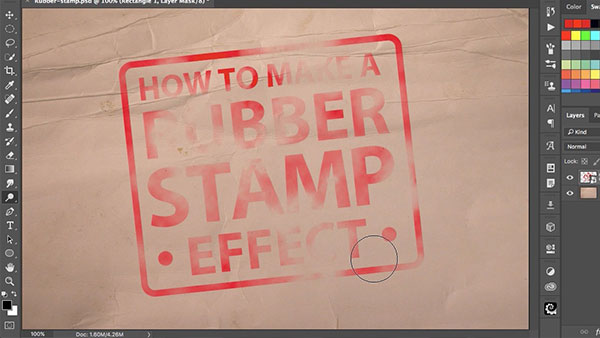

How to Make a Rubber Stamp Effect in Photoshop

You can turn just about any artwork, logo, or text into a rubber stamp by follow...

Better Tools for Tones: Why I Don’t Look at the Histogram

The histogram—the graph of tonal levels you see in photo-editing software—helps...