Spacing Out

Display type is supposed to be attention-grabbing, and an easy means to that end is to puff up the spaces between characters, a technique known as letterspacing. At text sizes, loose character spacing can camouflage a variety of composition sins, such as alternately loose and tight lines, but at large type sizes, spacing problems become more dramatic and more obvious. So while letterspacing may be good for grabbing readers’ eyes, it’s no shortcut to pleasing them. Follow these basic rules to avoid the most common pitfalls.

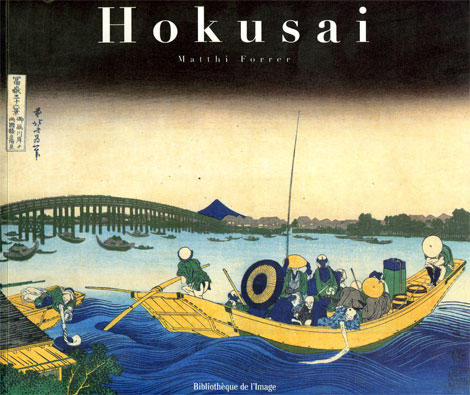

1. Letterspacing doesn’t hide bad kerning. At display sizes, intercharacter spacing problems that may be subtle at text sizes suddenly lose their subtlety. When you exaggerate the spacing between characters, minor kerning problems get magnified, too. In Figure 1, whoever set the book’s cover type assumed that any kerning problems would be lost amid the jumbo spaces opened up between the characters. Not so.

Figure 1. It’s clear at a glance that the first four characters of Hokusai’s name follow a different spacing scheme that the last four, and the net effect is a sloppy appearance.

I base that opinion on the fact that even at normal tracking values, the word “Hokusai,” when set in Didot Bold as in the book, displays obvious kerning problems, as shown in Figure 2. Being set in reverse disguises some of the uneven spacing, but it still exists, and it jumps out even more on the book’s title page, where the same type appears in black on white.

Figure 2. In the first pair, I set the top name at its natural spacing and opened the tracking of the one below by 250/1000 em (approximately the setting seen in Figure 1). In the second pair, I hand-kerned the upper version until its spacing was correct. But when I gave that version a 250/1000 tracking increase, it reveals that kerning problems persist. As shown in the final sample at the bottom, the only solution is to kern after the tracking adjustments have been made. In this case, after kerning, its tracking has been opened up to 280/1000 to get it to set to the same width as the original book-cover type.

The lesson here is that while hand-kerning before adjusting tracking may be a workable technique work for normal display type (where tracking changes are modest), it won’t work for letterspaced type. When character spaces are grossly exaggerated, you have to save kerning for the final step.

2. Forced justification isn’t the whole solution. The easiest way to letterspace a line of type would seem to be simply to force-justify it. (InDesign calls this option “justify all lines;” QuarkXPress simply calls it “forced.”) This causes the spaces in a single line of type ending with a return (that is, a one-line paragraph) to expand to fill the measure. This may work when the line consists of a single word, in which case the character spaces are equally expanded. But if the line contains one or more word spaces, your program will expand the character spaces only to the limit you’ve set in your hyphenation and justification (h&j) preferences. Once that limit’s been reached, all other necessary stretching is applied to the word spaces, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Unless your program’s h&j settings allow gross exaggeration to character spaces (something you won’t want for text settings), forced justification will do most of its spacing expansion at word spaces. That’s the case here. Programmers have correctly reasoned that when h&j values can’t be respected, it’s better to allow words to be readable and have distorted word spaces than to allow words to be stretched into illegibility.

There are ways around this. The easiest is to eliminate word spaces in the line altogether. Then, once you’ve forced-justified the line, you can create proportionally appropriate word spaces by adding a combination of fixed spaces: ems, ens, and thins. This process is illustrated in Figure 4. As the fixed word spaces grow, the character spaces shrink accordingly. It’s a far easier technique than adjusting your h&j settings to allow word and character spaces to automatically expand proportionally.

Figure 4. I set the upper sample with normal character and word spacing and then force-justified it. Most of the stretching is applied to the word spaces. In the middle sample, I deleted the word spaces. In the version on the bottom, I inserted fixed spaces to create word spaces. Forced justification does not affect the widths of fixed spaces.

The catch is that when you create a line of type with no word spaces, your program will see it as a single word. Both QuarkXPress and InDesign have controls by which you can allow or disallow the forced justification of a line consisting of a single word. In QuarkXPress, the default setting (found in the Edit/H&Js/Edit dialog box) is to allow single words to be so stretched. In InDesign, it’s the opposite: The default setting (found by selecting Justification from the Paragraph palette menu) is to disallow single-word forced justification. In either case, you can build your preference into a paragraph style sheet for letterspaced type.

You’ll find InDesign’s fixed spaces by going to Type > Insert White Space. In QuarkXPress, go to Utilities > Insert Character > Special.

3. Punctuation in letterspaced type requires special attention. Forced justification causes equal amounts of space to be added between all characters, and this leaves punctuation marks looking like they’re drifting off into space. Apostrophes, exclamation and question marks, commas, and points of ellipsis all look badly positioned when spaced automatically, as you can see in Figure 5.

Figure 5. In the top sample, set automatically by the program, the apostrophe and question mark are too spaced out. In the lower sample, I inserted word spaces between all the characters on the line and replaced some with fixed spaces to draw the punctuation marks back into more natural positions.

To restore proper spacing, first add word spaces between all the characters on the force-justified line. Now substitute fixed spaces for the troublesome spaces around punctuation marks.

Again, because fixed spaces can’t be stretched, they’ll be narrower than the artificially expanded spaces. Once your spacing is close to correct, you can hand-kern the spaces to get them just so.

Frederick Goudy once said that anyone who would letterspace type would steal sheep. That seems a bit grumpy of old Fred, but there’s no doubt that when you allow spacing to become wildly exaggerated, you’re drifting into the nether regions of the typographic universe. You can’t rely on your programs alone to chart a path to readability. As always, you have to rely on your eyes and good judgment to avoid becoming lost in space.

If you read this, and want to rate your kerning skills you probably will enjoy this game. (I didn’t make it but share it anyway)

type.method.ac

When I have several words to force justify, I put a character between them then use Character Styles to change the spacers to no color. This is in InDesign. Works pretty well.

I seem to remember Fred was speaking of lower case text. U/C is much nicer spaced.

In the Alphabet and the Elements of Lettering, F. W. Goudy said something like anyone who would letter space lower case would suck eggs.

Sucking eggs?

No, it was “steal sheep.”

And these are words one should always live by.

How do I kern a pair to my liking in any given font as a default? ie: My body text period close quote (.”) is very tight and I’d like to change it rather than doing a search and paste (search and replace doesn’t hold the new kerning). I have a few other pairs like this so I’d really like to change the defaults somehow.