The Art of Business: Do Unto Others

You’re creating a brochure or Web site, and you want to include material or pieces of material created by others: graphics, photographs, text, music, Flash animation, whatever.

Is it legal? Probably not. Can you get away with it? Probably so. Do you want to take the chance? That is the $64,000 question, according to attorney Richard Stim, author of the excellent resource book, Getting Permission: How to License & Clear Copyrighted Materials Online & Off.

“The fact is, there is no copyright police and it is up to the copyright holder to enforce his or her copyright,” says Stim. “As a result, very few people actually get sued for copyright infringement. On the other hand, if someone decides to sue you for copyright infringement, you’re in for a costly and protracted legal battle.”

Stim suggests that it’s always best to get permission (his book includes sources, plus permission forms on an accompanying CD-ROM). But should you decide to use material without permission, Stim suggests you ask yourself a few questions to determine, aside from the moral implications, your risk of liability.

* Will the copyright holder be able to recognize the copyrighted material?

* Will the final product be highly publicized and likely seen by the copyright holder?

* Will the copyright owner care?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, think twice before using copyrighted material without permission. But read on, because you still may be on solid legal ground.

Fair Play

To strike a balance between the public’s need to be well-informed and the copyright owners’ rights to profit from their creativity, Congress passed a law authorizing the use of copyrighted materials in certain circumstances deemed to be fair — even when the copyright owner doesn’t give permission.

Copyright law allows for the fair use of copyrighted material in limited and transformative purposes. The fair use rule recognizes that society can often benefit from the unauthorized use of copyrighted materials when the purpose of the use serves the ends of scholarship, education, or an informed public. For example, scholars must be free to quote from their research resources in order to comment on the material.

But because the law is vague, it’s often difficult to know whether a court will consider a proposed use to be fair. The fair use statute requires the courts to consider the following questions in deciding this issue:

- Is it a competitive use? (In other words, if the use potentially affects the sales of the copied material, it’s usually not fair.)

- How much material was taken compared to the entire work of which the material was a part? (The more someone takes, the less likely it is that the use is fair.)

- How was the material used? Is it a transformative use? (If the material was used to help create something new, it’s more likely to be considered a fair use than if it’s merely copied verbatim into another work. Criticism, comment, news reporting, research, scholarship and non-profit educational uses are most likely to be judged fair uses. Uses motivated primarily by a desire for a commercial gain are less likely to be fair use).

As a general rule, if you’re using a small portion of somebody else’s work in a non-competitive way and the purpose for your use is to benefit the public, you’re on pretty safe ground. On the other hand, if you take large portions of someone else’s expression for your own purely commercial reasons, the rule usually won’t apply.

Internet Changing Everything

But the laws are changing, according to Stim, affected by — and in response to — the Internet.

In 2003, for example, a court ruled that permission was not needed to reproduce thumbnail copies of photographs on a Web site.

“Arriba Soft Corporation operated an Internet search engine that displayed thumbnails copied from other web sites,” said Stim. “Kelly, a photographer, discovered that his photos were part of Arriba’s database and filed suit for copyright infringement. The court of appeals held that using thumbnail reproductions of copyrighted photographs on a Web site was a fair use because the use was ‘transformative’ and did not interfere with the photographer’s economic expectations.”

To the photographer, thumbnails of his pictures didn’t seem very different from full-sized representations. So how do you define “transformative” use? “It’s a particularly challenging question in the digital age where it is so easy to transform everything,” says Stim. “Unfortunately, no hard-and-fast rules apply, and they never will because lawmakers wanted fair use to be open to interpretation, and the nature of technology is always changing.”

What if you use only a bit of text or a small corner of a photograph? While it’s true that copying a small amount of anything is technically not copyright infringement, it’s difficult to know where “small copying” ends and copyright infringement begins. There are no dramatic lines in the sand.

“Legally, only the creator of the work has the right to modify that work,” Stim says. “So even if you alter the photograph beyond recognition by cropping it, coloring it, and adding elements here and there, technically it’s still considered copyright infringement.”

On the other hand, says Stim “do not assume that Web-based clip art, shareware, freeware, or materials labeled ‘royalty-free’ or ‘copyright-free’ can be distributed or copied without authorization.”

Stim suggests that you read the “Click to Accept” agreement or “Read Me” files that often accompany such materials.

Permissions Are Easy

But why fret over vague definitions? It’s easy to license most material, and in many cases, it will be free or almost free. If you know who the copyright owner is, contact the owner directly. If you don’t, ask the Copyright Office to conduct a search of its records. There’s more information about the permission search in the Copyright Office’s Circular 22.

Copyright licensing is good business practice, and if your client balks over the added expense or time necessary to obtain permission, explain the possible consequences — monetary damages and a halt to distribution. (Stim also suggests that if you’re doing work for hire, you review, and perhaps modify, the paragraph that covers indemnifications and strike any warranty that all work is original).

In truth, unless there’s a good deal of cash or prestige at stake, most artists and writers won’t take the time, energy, and money to sue you or your client for copyright infringement, according to Stim.

Unfortunately, this may lead to the belief that copyright infringement is somehow a condonable action. And it’s not. You don’t want people to rip off the fruits of your creativity, so it’s only right that you not steal others’ work.

This article was last modified on July 11, 2023

This article was first published on May 9, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Use the New Selection Brush Tool in Photoshop

Learn how to use Photoshop’s new Selection Brush tool to manually refine a selec...

dot-font: Type You Can Use Again and Again

dot-font was a collection of short articles written by editor and typographer Jo...

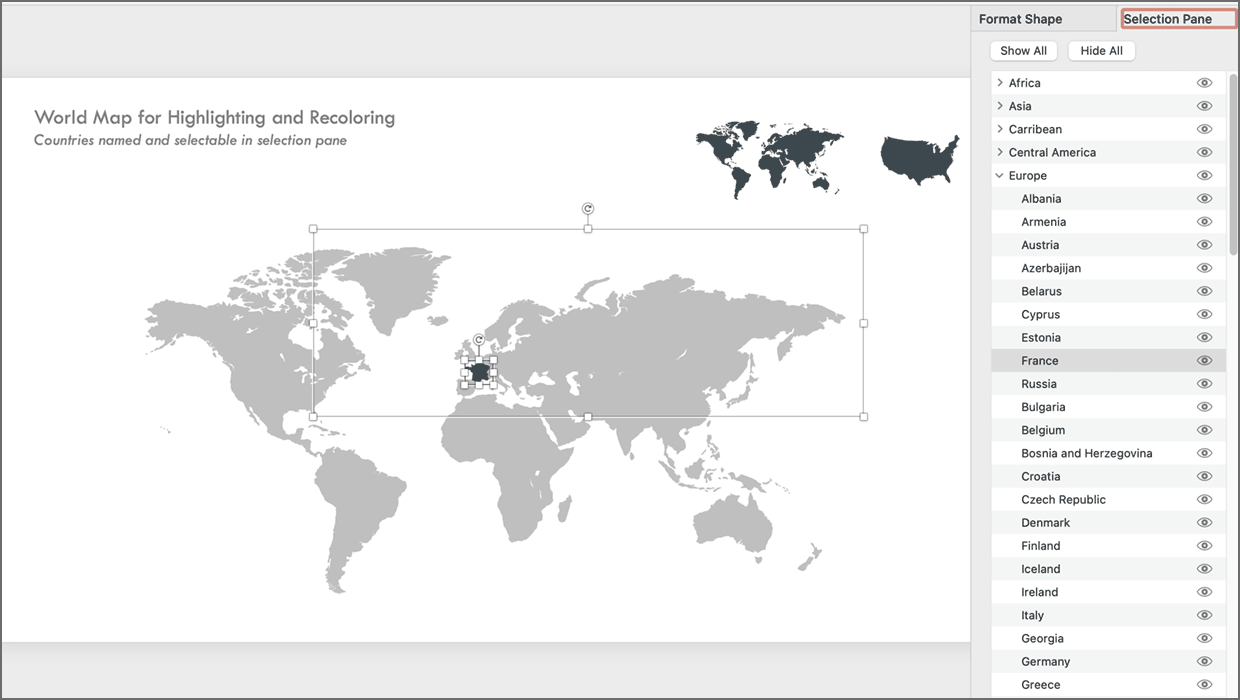

PowerPoint Maps Template

This PowerPoint template contains maps of the United States and world countries...